Students with disabilities often snared by subjective discipline rules

For the first 57 minutes of the basketball game between two Bend, Oregon, high school rivals, Kyra Rice stood at the edges of the court taking yearbook photos. With just minutes before the end of the game, she was told she had to move.

Kyra pushed back: She had permission to stand near the court. The athletic director got involved, Kyra recalled. She let a swear word or two slip.

Kyra has anxiety as well as ADHD, which can make her impulsive. Following years of poor experiences at school, she sometimes became defensive when she felt overwhelmed, said her mom, Jules Rice.

But at the game, Kyra said she kept her cool overall. Both she and her mother were shocked to learn the next day that she’d been suspended from school.

“OK, maybe she said some bad words, but it’s not enough to suspend her,” Rice said.

The incident’s discipline record, provided by Rice, lists a series of categories to explain the suspension: insubordination, disobedience, disrespectful/minor disruption, inappropriate language, non-compliance.

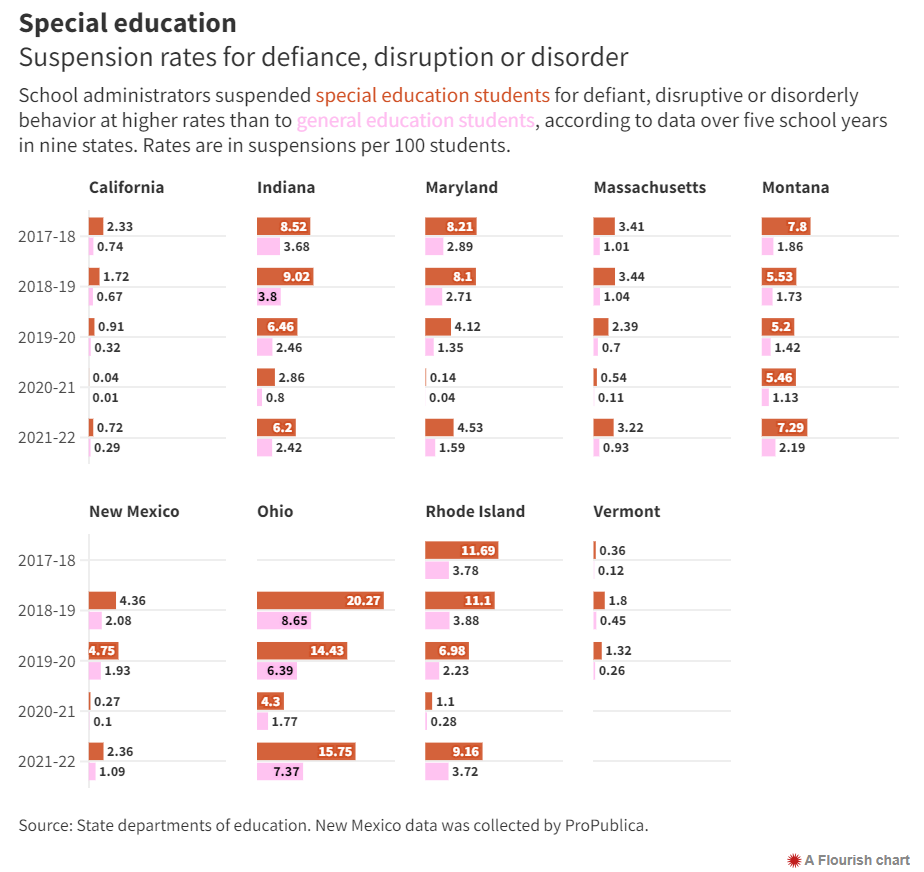

Broad and subjective categories like these are cited hundreds of thousands of times a year to justify removing students from school, a Hechinger Report investigation found. The data show that students with disabilities, like Kyra, are more likely than their peers to be punished for such violations. In fact, they’re often more likely to be suspended for these reasons than for other infractions.

For example, between 2017-18 and 2021-22, Rhode Island students with disabilities were, on average, two and a half times more likely than their peers to be suspended for any reason, but nearly three times more likely to be suspended for insubordination and almost four times more likely to be suspended for disorderly conduct. Similar patterns played out in other states with available data including Massachusetts, Montana and Vermont.

Federal law should offer students protections from being suspended for behavior that results from their disability, even if they are being disruptive or insubordinate. But those protections have significant limitations. At the same time, these subjective categories are almost tailor-made to trap students with disabilities, who might have trouble expressing or regulating themselves appropriately.

Districts have wide discretion in setting their own rules and many students with disabilities quickly earn reputations at school as troublemakers. “Unfortunately, who gets caught up in a lot of the vagueness in the codes of conduct are students with disabilities,” said attorney Robert Tudisco, an expert with Understood.org, a nonprofit that provides resources and support to people with learning and attention disabilities.

Related: When your disability gets you sent home from school

Students on the autism spectrum often have a hard time communicating with words and might yell or become aggressive if something upsets them. A student with oppositional defiant disorder is likely to be openly insubordinate to authority, while one with dyslexia might act out when frustrated with schoolwork. Students with ADHD typically have a hard time controlling their impulses.

Kyra’s disability created challenges throughout her school career in the Bend-La Pine School District. “Nobody really understood her,” Rice said. “She’s a big personality and she’s very impulsive. And impulsivity is what gets kids in trouble and gets kids suspended.”

Kyra, now 17, said that too few teachers cared about her individualized education program, or IEP, a document that details the accommodations a student in special education is granted. She’d regularly butt heads with teachers or skip class altogether to avoid them. Her favorite teacher was her special ed teacher.

“She understood my ADHD and my other special needs,” Kyra said. “My other teachers didn’t.”

Scott Maben, district spokesperson, said in an email he could not comment on specific disciplinary matters because of privacy concerns, but that the district had a range of responses to deal with student misconduct and that administrators “carefully consider a response that is commensurate with the violation.”

In Oregon, “disruptive conduct” accounted for more than half of all suspensions from 2017-18 to 2021-22. The state department of education includes in that category insubordination and disorderly conduct, as well as harassment, obscene behavior, minor physical altercations, and “other” rule violations.

Disruptive behavior is the leading cause of suspensions because of its “inherently subjective nature,” the state department of education’s spokesperson, Marc Siegal, said in an email. He added that the department monitors discipline data for special education disparities and works with school districts on the issue.

The primary protections for students with disabilities come from the federal government, through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA. But that law only requires districts to examine whether a student’s behavior stems from their disability after they have missed 10 total days of school through suspension.

At that point, districts are required to hold a manifestation hearing, in which officials must determine whether a student’s behavior was the result of their disability. “That’s where it gets very gray,” Tudisco said. “What happens in the determination of manifestation is very subjective.”

In his experience, he added, the behavior is almost always connected to a student’s disability, but school districts often don’t see it that way.

“Manifestation is not about giving Johnny or Susie a free pass because they have a disability,” Tudisco said. “It’s a process to understand why this behavior occurred so we can do something to prevent it tomorrow.”

Related: Senators call for stronger rules to reduce off-the-books suspensions

The connections are often much clearer to parents.

A Rhode Island mother, Pearl, said her daughter was easily overwhelmed in her elementary school classroom in the Bristol Warren Regional School District. (Pearl is being referred to by her middle name because she is still a district parent and fears retaliation.)

Her child has autism and easily experiences a sensory overload. If the classroom was too loud or someone new walked in, she might start screaming and get out of her seat, Pearl said. Teachers struggled to calm her down, as other students were escorted out of the room.

Sometimes, Pearl was called to pick up her daughter early, in an unrecorded informal removal. A few times, though, she was suspended for disorderly conduct, Pearl recalled.

Between 2017-18 and 2020-21, students with disabilities in the Bristol Warren Regional School District made up about 13 percent of the student body, but accounted for 21 percent of suspensions for insubordination and 30 percent of all disorderly conduct suspensions.

The district did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The Rhode Island Department of Education collects data on school discipline from districts, but special education and discipline reform advocates in the state say that the agency rarely acts on these numbers.

Department spokesperson Victor Morente said in an email that the agency monitors discipline data and is “very clear that suspension should be the last option considered.” He added that the department has published resources about alternatives to suspension and discipline specifically for students with disabilities.

A 2016 state law that limits the overall use of out-of-school suspensions also requires that districts examine their data for inequities. Districts that find such disparities are supposed to submit a report to the department of education, said Hannah Stern, a policy associate at the Rhode Island American Civil Liberties Union.

Her group submits public records requests for copies of their reports every year, but has never received one, she said, “even though almost every single school district exhibits disparities.”

Related: Sent home early: Lost learning in special education

Pearl said that her daughter needed one-on-one support in the classroom instead of punishment. “She’s autistic. She’s not going to learn her lesson by suspending her,” Pearl said. “She actually got more scared to go back. She actually felt very unwelcome and very sad.”

Students with autism often have a hard time connecting their actions to the punishment, said Joanne Quinn, executive director of The Autism Project, a Rhode Island-based group that offers support to family members of people with autism. With suspension, “there’s no learning going on and they’re going to do the same thing incorrectly.”

Quinn’s group provides training for schools throughout Rhode Island and beyond, aimed at helping teachers understand how the brain functions in people with autism and offering strategies on how to effectively respond to behavior challenges that could easily be labeled disobedient or disorderly.

Federal law provides a road map for schools to improve how they respond to misconduct related to a student’s disability. Schools should identify a student’s triggers and create a behavior intervention plan aimed at preventing problems before they start, it says.

Related: How a disgraced method of diagnosing learning disabilities persists in our nation’s schools

But, doing these things well requires time, resources and training that can be in short supply, leaving teachers feeling alone, struggling to maintain order in their classrooms, said Christine Levy, a former special education teacher and administrator who works as an advocate for individual special education students in the Northeast, including Rhode Island.

Levy recently worked with a student with disabilities who was suspended after he tickled a peer at a locker on five straight days. But, she said, the situation should have never reached the point of suspension: Educators should have quickly identified what the boy was struggling with and set a plan in motion to help him, including modeling appropriate locker conduct.

Had this boy’s teachers done that, the suspension could have been avoided. “The repair of that is so much longer and so much harder to do versus, let’s catch it right away,” she said.

Many parents described similar situations, though, in which a child routinely got in trouble for repeated behavior. When Michelle Gomes’s daughter became upset in her kindergarten classroom, she’d often run out and refuse to come back in. Sometimes, she’d tear things off the walls.

“Whenever she gets like that, it’s hard to see,” Gomes said. “I hurt for her. It’s like she’s not in control.”

Gomes received regular calls from Cranston Public School officials to come pick her daughter up. A couple of times, the child was formally suspended, Gomes said. The school described her as a safety risk, Gomes recalled.

“She obviously doesn’t feel safe herself,” she said.

Cranston Public Schools did not respond to requests for comment.

Gomes’s daughter had a speech delay and anxiety and qualified for special education services. A private neurological evaluation concluded that she was compensating for that delay with her physical responses, Gomes said.

This can be a common cause of behavior challenges for students with disabilities, experts say.

“Behavior is communication,” said Julian Saavedra, an assistant principal and an expert at Understood.org.* “The behavior is trying to tell us something. We as the IEP team, the school team, have to dig deeper.”

On her own, Gomes found strategies that helped. Gomes’ child struggled with transitions, so they’d go over her day in advance to prepare her for what to expect. A play therapist taught both her and her daughter breathing exercises.

Her daughter was switched to another district school where a social worker would sometimes walk the girl to class. When the child got worked up, she’d sometimes be allowed to sit with that social worker or in the nurse’s office to calm down. That helped, but sometimes, those staff members weren’t available.

In the end, Gomes moved her daughter to a school outside the district that was better equipped to help the girl deescalate. Her behavior problems lessened and she started enjoying going to school, Gomes said.

But Gomes still can’t understand why more teachers weren’t able to help her child regulate herself. “Do we need retraining or do we need new training?” she said. “Because this is mind-blowing to me, not one of you can do that.”

Note: The Hechinger Report’s Fazil Khan had nearly completed the data analysis and reporting for this project when he died in a fire in his apartment building. USA TODAY Senior Data Editor Doug Caruso completed data visualizations for this project based on Khan’s work.

CORRECTION: This article has been updated with the correct spelling of Julian Saavedra’s name.

This story about suspension of students with disabilities was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Written By: Sarah Butrymowicz, Fazil Khan, and Sara Hutchinson